George Lohay’s New Paper Published

Paper Title: Genetic evidence of population subdivision among Masai giraffes separated by the Gregory Rift Valley in Tanzania (link)

RISE’s newest team member, George Lohay, has already begun forging new paths and findings forward to advance the conservation of African wildlife. George has had a lot to celebrate lately – he joined RISE as a Research Scientist in mid-May, and recently, his study on the genetic subdivision of Masai giraffes was published in the esteemed journal Ecology and Evolution.

Starting in 2019, George and a team of researchers from Penn State University examined the genetic structure of Masai giraffe populations in the Serengeti and Tarangire ecosystems. These two ecosystems are geographically separated by Tanzania’s Gregory Rift Valley, and their study examined if and how the giraffe populations of each interact with one another.

The research initiative responded, in part, to mounting concerns about the declines in global giraffe populations. With widespread illegal hunting and habitat degradation from human settlements and infrastructure, the species so characteristic of this landscape is beginning to dwindle. In fact, in the past 30 years alone, it is estimated that Masai giraffe populations – a species endemic to southern Kenya and Tanzania that once numbered around 70,000 – have shrunk by an estimated 50%, earning them a spot on the IUCN’s endangered subspecies list in 2019 (Lohay et al., 2023).

When asked about his inspiration for the study, George explained that the significant decline in Masai giraffes means that the species is especially sensitive, and in order to best protect them, we need to understand as many dynamics affecting them as quickly as possible. George immediately knew what questions he wanted to investigate about the Masai giraffe, especially because he completed a similar study on elephant populations in 2018 as part of his PhD. In addition, George mentioned that he has always had a personal affinity for giraffes: “They are very calm animals…they communicate a lot with each other, and they form long-term friendships that some people think might last their entire lifetimes. That always made me really love them.”

Responding to the global call to understand this endangered species better, George and his team deployed to Tanzania three separate times, each for a period of two to three months. Upon arriving in the field, the researchers would start their data collection process; they would track Masai giraffes, patiently wait for nature to take its course, and eventually collect giraffes’ fecal samples for analysis. In 2021, the team realized that the study could benefit from giraffes’ tissue samples in addition to the fecal samples, at which point they started to work with a veterinarian from Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute to dart and safely extract small samples for the research.

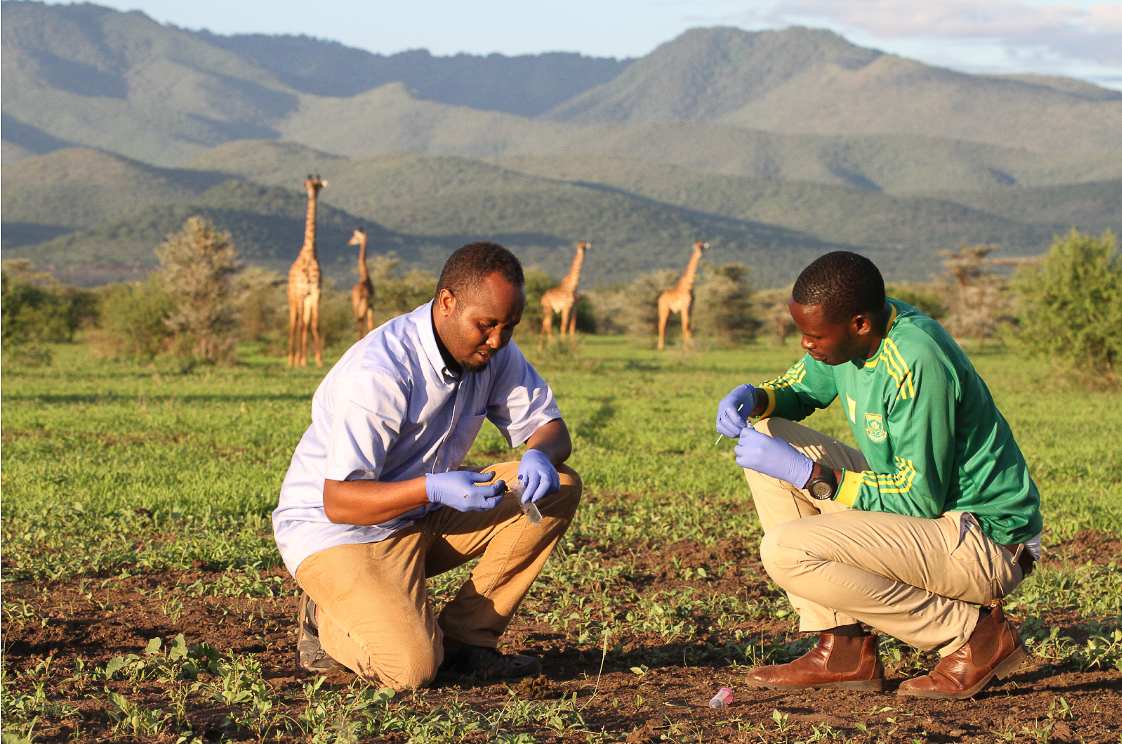

Dr. George Lohay and Emmanuel Kimaro collecting giraffe fecal samples. (Photo: James Madeli)

Ultimately, the study indicated that the giraffes are more jeopardized than previously thought. George and his team found that the two populations have not been interacting or interbreeding, resulting in two genetically different populations. They estimated that female giraffes have not migrated over the Rift Valley from one ecosystem to the other for the past 289,000 years, and males have not migrated for at least the last few thousand years. The Masai giraffes were found to face both natural habitat fragmentation from the harsh and hard-to-climb escarpments of the Rift Valley, as well as from human encroachment on wildlife habitat. Unfortunately, this second type of ecosystem fragmentation can be observed across most of East Africa, as wildlife habitats are increasingly converted to other uses to support growing human populations.

Population migration and interbreeding are important for building ecological resilience because they facilitate genetic diversification, in effect, reducing populations’ sensitivities to diseases, genetic mutations, and other threats (McCormick, 2023). Concerningly, the study found indicators of inbreeding in each of the populations, a trend that reduces the genetic diversity and health of wildlife populations. This finding further reinforces the significance of this study and the urgency with which novel conservation initiatives are needed.

Highlighting the need to develop creative and effective conservation solutions specific to each of these separate populations, George explained: “[The results are] important because we now need to think about the Masai giraffe as an evolutionary significant unit. Instead of thinking about 35,000 giraffes remaining in the wild, we are actually thinking that each unit is significant on its own and will require tailored, separate efforts to conserve each population unit as they are inherently not the same.” George also highlighted the importance of wildlife corridors to these population changes, emphasizing that without conservation, the few remaining wildlife corridors will be blocked completely, creating additional barriers for wildlife.

In the future, George hopes to see giraffes better protected and understood. George and his collaborators from Wild Nature Institute and Penn State University have already taken measures toward new research on the connectivity between giraffe populations in the Northern and Southern regions of Tanzania. He hopes to see more researchers, especially young ones, use genetic tools in research: “By using genetic tools, we can provide information to conservation organizations or governments about connectivity that can help develop policy to protect these animals in the long-term. I think we need to keep encouraging our youth to get involved in research because it has years to go and will inform decision makers.”

By gathering motivated researchers like George, who use research as a mechanism to advocate for and improve conservation, we hope that this iconic species and others like it will have a chance to rebound in the future.

George is especially grateful for the dedicated research team he collaborated with to complete this study. Specifically, George collaborated with principal investigators: Derek Lee, Associate Research Professor of Biology at Penn State University and Principal Scientist of Wild Nature Institute, and Douglas Cavener, Professor of Biology at Penn State University. In addition, he mentioned the incredible contributions of Monica Bond, Principal Scientist at Wild Nature Institute, as well as other researchers from Penn State University, Lan Wu-Cavener, David L. Pearce, and Xiaoyi Hou.

To donate to GF’s applied research programs, click here.